Behaviours and Symptoms

This is part two of a three part series on Trauma, PTSD & Education. If you haven't read the first part yet - click here to do so, then jump back and carry on here!

To identify and diagnose trauma/PTSD can be quite tricky for professionals. For example, many young people we work with come with a range of diagnosed conditions. These conditions can often be symptoms of PTSD, but are not addressed as such because the cause or root has not been fully investigated.

Parents, carers, teachers and doctors often want to put some kind of support in place, and the easiest and quickest way to enable this, is to get a recognised (more easily quantifiable) diagnosis. Unfortunately this is often not enough to actually start to heal the underlying cause.

Taking medication to ease "conditions" can also mask PTSD, often behaviours will re-emerge as they serve as coping mechanisms. Behaviours may become worse when we try to restrict coping mechanisms. These patterns need to be addressed at the relational (Limbic system) and then developmental (Neo Cortex) levels (click to read more about this in part 1 of this series).

Conversely we cannot automatically assume that all unusual or anti-social patterns of behaviour are based in trauma. Long-term medical and psychological investigation/support is needed to get to the root of these sorts of issues.

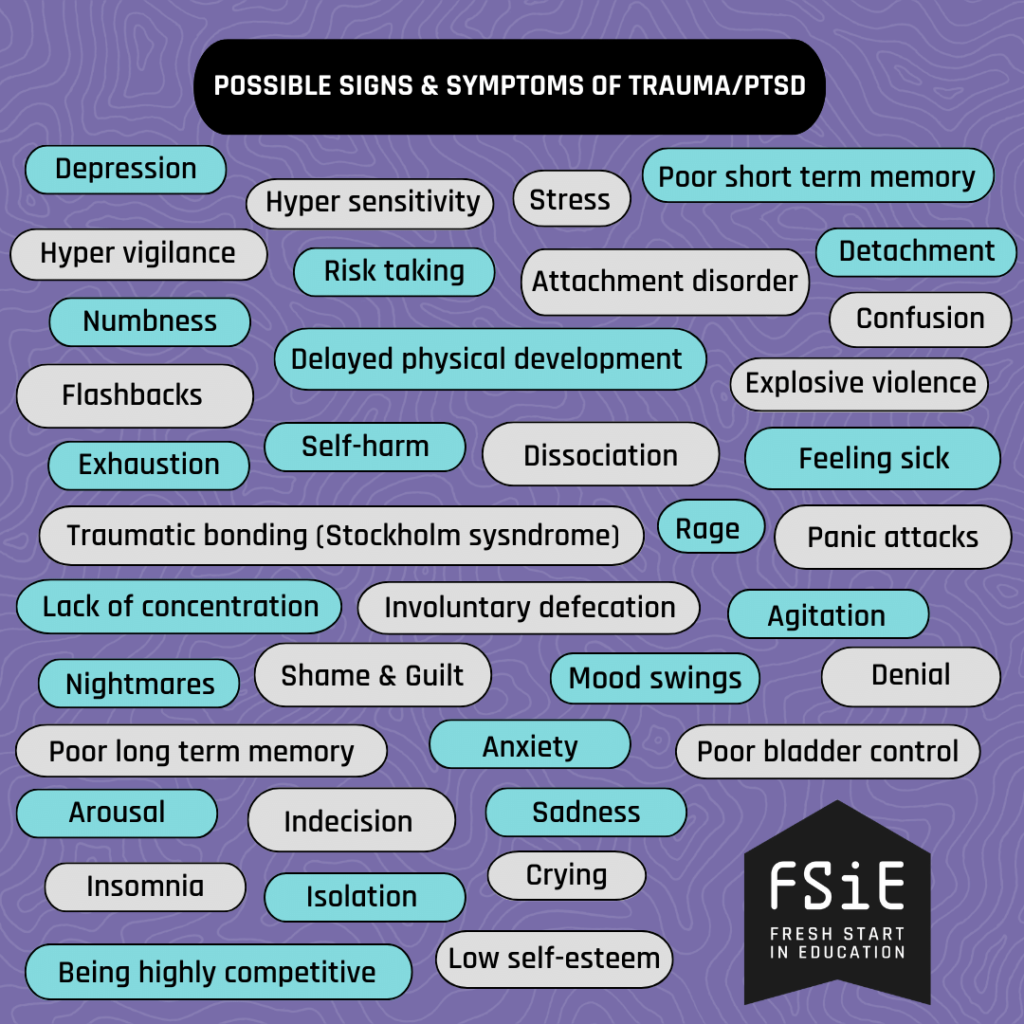

Thinking back over the many years I've worked with young people with special educational needs, I could list hundreds of behaviours or symptoms that were very likely the result, or expression of, trauma/PTSD. From my experience here are some of the most common in the adjacent image.

There are many more that could be mentioned.

As you can probably see from this list, it is difficult to identify common threads. The only commonality I can identify is that emotional dysregulation is a feature of all these symptoms/behaviours.

Everyone is different and trauma can impact each person differently. Trauma response is the brain in survival mode and therefore people may behave in unexpected ways. Logic and emotions may appear wild or inconsistent. It is a normal human response to abnormal events.

When you work with a child and witness behaviours that are anti-social or unpleasant, maybe stop and think; what are they trying to change? What are they needing to happen? All behaviour is communication.

Overwhelmed by the symptoms of trauma, many turn to alcohol or drugs to control or block our memories or unwanted thoughts or sensations. Also, a very common issue with trauma is unclear or unreliable memory. A person with PTSD might have a sense of confusion around events and timelines, with gaps where traumatic events happened. This can also effect the short term memory, as triggers, flashbacks and emotional peaks may negate recent (seemingly innocuous) events. From the outside a person might just appear unfocused or in a dreamlike/distracted state. This can often be misinterpreted as laziness, lack of commitment or intelligence; which is very important to bear in mind when teaching young people.

“Eliminating the symptoms that accompany emotional distress might provide short-term solutions, allowing, for instance, an impulsive child to sit at a desk or a depressed adult to get out of bed in the morning. But if these problematic behaviors serve an adaptive function, are actually a way of coping or holding oneself together, then if the relational and developmental context of these behaviors is not addressed, we should not be surprised if they reappear in different and sometimes more problematic forms.”

― Ed Tronick, The Power of Discord: Why the Ups and Downs of Relationships Are the Secret to Building Intimacy, Resilience, and Trust

Part 3 - How to help people heal from trauma - Coming soon!

About the author