Undoubtedly, our understanding of autism has developed over the last two decades; however, the language we use to describe autism or an autistic child’s ‘needs’ in education today, suggests we remain some distance from achieving inclusivity and this could be having more of a negative effect than we first thought.

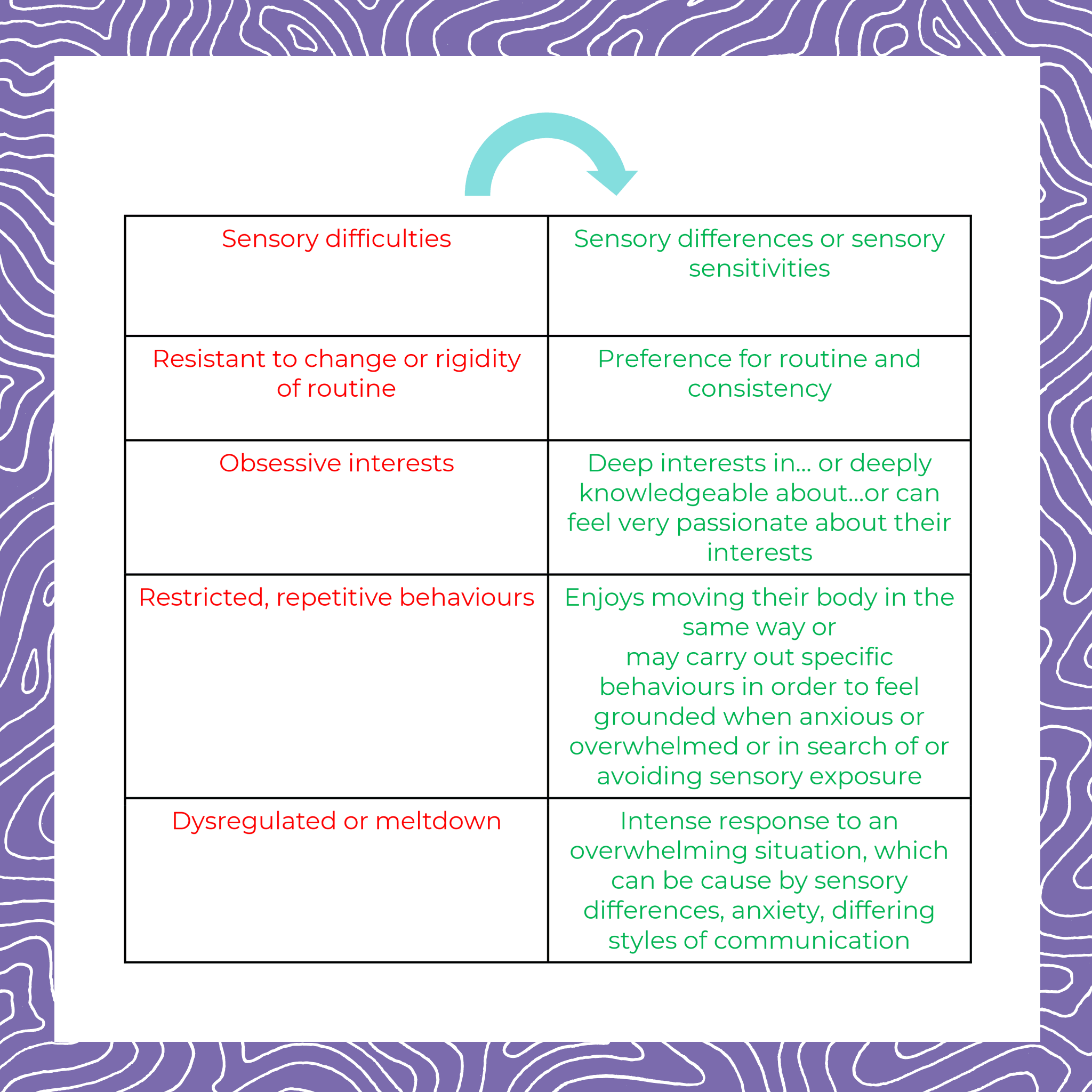

Our choice in language can be influenced by our attitudes and perspectives of autism. Generally speaking, our language can be aligned with either the medical model of disability or neurodiversity. The language used in accordance with the medical model is deficit focused, and terms such as “persistent difficulties”, “restricted”, “abnormal”, “failure of” and “absence of” can be seen across professional documentation (e.g. progress reports, EHC Plans, behaviour support plans etc.) and the diagnostic criteria for autism (DSM-5 and ICD-11). Alternatively, the language used in line with neurodiversity begins to acknowledge and more importantly celebrate neurological differences. Shifting our focus to perceiving autism as an alternative way of thinking, viewing and experiencing the social world; because after all, there is certainly not just one correct neurocognitive function.

Our choice in language can have a significant impact on how we as professionals view an autistic child and their capabilities within education, but also how others in school (including autistic children themselves) and the wider community see and understand autism. Though, a child does not need to receive a permanent or fixed term exclusion to feel excluded from school or education; what about social exclusion, being asked to leave a lesson for a specific intervention, not being included in an activity because someone has decided they cannot cope before being given the option to decide for themselves? All of which can inhibit a child’s academic progress, personal and social development, and lead to poor mental health.

Inclusion is more than just a child having the right to access mainstream education, it is about having the opportunity to be socially integrated within a school community, be fully understood by all within their educational provision, have access to high quality personalised education and lifelong learning. Re-evaluating our choice in language is a small adjustment to make in our journey towards an inclusive world for autistic children, young people, and adults; yet the impact of this can be significant, developing self-confidence and self-belief.

Acknowledgements & Further Reading

These ideas have been developed following the reading of Inclusive Education for Autistic Children:

Helping Children and Young People to Learn and Flourish in the Classroom by Dr Rebecca Wood,

NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and How to Think Smarter About People Who Think Differently by Oliver Sacks

The Neurodiverse Classroom: A Teachers Guide to Individual Learning Needs and How to Meet Them by Victoria Honeybourne.

In addition to this, attending lectures by Dr Rebecca Wood and Tanya Cotier at the University of East London as part of my MA in SEN course.

I would like to specifically thank my supervisor, Dr Rebecca Wood, whose support, guidance and insight into this subject continues to steer me long after my dissertation. Her work within this topic has inspired me and in particular the below book;

Inclusive Education for Autistic Children: Helping Children and Young People to Learn and Flourish in the Classroom by Dr Rebecca Wood.